The first time I tried an Imada Shuzo (brewery) sake was in 2014 when we opened our bottle shop in Oakland. The savory acidity of the Fukucho Forgotton Fortune Junmai made my mouth water, and I have been a convert ever since. I love having Forgotton Fortune with oysters and manila clams, both abundant in Northern California. And it’s no accident that this sake pairs so well with oysters, as Imada Shuzo is located in Hiroshima Prefecture, a region famous for oysters.

The first time I tried an Imada Shuzo (brewery) sake was in 2014 when we opened our bottle shop in Oakland. The savory acidity of the Fukucho Forgotton Fortune Junmai made my mouth water, and I have been a convert ever since. I love having Forgotton Fortune with oysters and manila clams, both abundant in Northern California. And it’s no accident that this sake pairs so well with oysters, as Imada Shuzo is located in Hiroshima Prefecture, a region famous for oysters.

Photo of Miho Imada courtesy of Imada Shuzo

Photo of Miho Imada courtesy of Imada Shuzo

Can you give me a brief history of the brewery?

The village of Akitsu in Hiroshima Prefecture, where the Imada Sake Brewery is located, is a quiet place facing the Seto Inland Sea. Since long ago, it has been famous as a village from which many toji and kurabito (brewery workers) come, and sake brewers from this region can be found at breweries in the village of Saijo in Hiroshima, known as the local “sake capital,” as well as all over the country. Akitsu was also the home of Sanzaburo Miura, a brewing expert that, in the late 1800s and early 1900s, taught many brewers how to brew with soft water and make high quality ginjo-shu. This is why people say that ginjo-shu was born in Hiroshima. Our name, Fukucho, was given to our sake by Mr. Miura. He is someone I consider to be my inspiration and mentor.

The entrance of Imada Sake Brewery, courtesy of Imada Shuzo

The entrance of Imada Sake Brewery, courtesy of Imada Shuzo

How did you get into sake-making?

In the winter of 1993 I enrolled in the National Research Institute of Brewing “crash course” of sake production. After just four months of studying the foundation of sake brewing, I returned in the fall of 1994 to my family’s brewery to start working under their toji at the time. Around 2000, the toji retired and I assumed the role.

What do you think is the best trait to have to lead a team? What do you value most about teamwork?

Right now we are a team of seven. Teamwork is the most essential part of our success. I take a lot of care to make sure no one gets injured during the sake brewing process, and so that my employees trust me with their well-being, until the end of the season. When great sake is the result of our hard work, everyone can feel proud and joyful. The other part of inspiring my team is to make sure each individual knows that he/she is an essential part of the sake that is made here at my brewery.

Can you tell me more about why you chose the ancient rice strain Hattanishiki for Hattanso?

I chose Hattanso (Hattanso is the base heirloom rice varietal; Hattan Nishiki is actually a hybrid deriving from Hattanso) to make sake in order to make a sake that is a true craft sake, or jizake, that cannot be made anywhere else except for our family brewery.

Hattanso is native to Hiroshima prefecture, and if you trace back its roots, it is very, very old. This is not a rice that has been modified to accommodate the preferences of consumers; it is a rice that has chosen to thrive based on the growing conditions of Hiroshima. Before, we were growing Yamada Nishiki rice, but in order to reflect the true terroir of Hiroshima I began the cultivation of Hattanso.

The town in Hiroshima that my brewery is in, Akitsu, has a great history of local tojis gathering together to find a way to make sake out of soft water, even though sake that originated in Kyoto used harder water, utilizing different production methods. They succeeded in producing what is now known as ginjo-shu, sake made with rice polished to high levels and fermented with soft water – although they faced many challenges along the way. Because of these advancements in sake brewing, dating back from the generation of my great-grandfather, I am able to brew sake to this day. While carefully considering what Japanese people appreciate in craftsmanship and flavor, I am still making sake today along these same principles.

In the koji room. Photo courtesy of Imada Shuzo

In the koji room. Photo courtesy of Imada Shuzo

I have heard that there are only 20 other women brewers in Japan. Why do you think it’s important for brewers to come from different backgrounds?

It could be that there are only 20 female tojis in Japan. There are no public documents to reflect how many female tojis there are in Japan, so I cannot say for certain. However, I do feel that this number is increasing. The fact that there are so many different expressions of sake is part of the enjoyment of this beverage. The coast of Japan is so long from North to South, and the climate changes considerably, that I hope that the breweries located in these very different regions find ways of expressing their individuality through their sake.

How do you start your day in the morning?

Because so much of sake making is really washing and cleaning, every morning I boil a large amount of water for these purposes (this is after I wake up at 4am to walk my dog).

How do you end your day in the evening?

I check to make sure that everything in the brewery is in order, and there is no cause for worry, and also that the preparations for the next morning are in order (and then, before I finally go to bed, I take my dog for another walk).

We are celebrating women producers this month at Umami Mart. Who is a role model you have who is also a female?

It is difficult to explain why, but since I’ve been in my twenties I’ve been a big fan of a comic producer named Mari Kimura. I cannot simply describe my admiration for this person, but she is very down to earth, and there is a mysterious air about her.

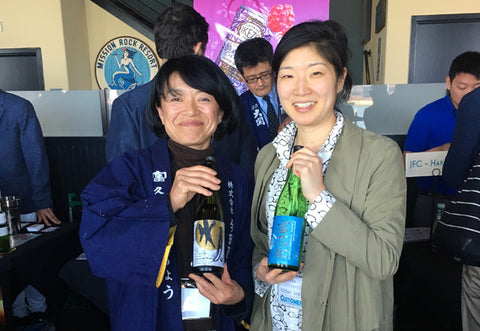

Miho Imada and me. Photo by Kayoko Akabori

Miho Imada and me. Photo by Kayoko Akabori

*Top photo of Miho Imada making sake, courtesy of Imada Shuzo

Comments (0)

There are no comments for this article. Be the first one to leave a message!