By Howie Correa

By Howie Correa

Within half a day of arrival from Ireland, I was excited to be heading out of endless Tokyo to visit a radiation testing facility at

Natural Harmony, a produce distribution site in Chiba. It was a trip that seemed to be at the heart of understanding the dilemma within this year's Japanese fall harvest, post-3/11, and all the ideas to be explored through OPENharvest.

Hours earlier, I had shared in the Ebisu-soaked joy and celebration side of being in Japan with a gang of creative, cross-continent collaborators. There was and is much to feel elated about, in recognizing connections through farms, food, wine and art. But zipping along in a sporty, yellow Volvo towards Chiba, to discuss radioactive contamination made one realize that Japan is dealing with very surreal, yet serious and specific everyday fears.

On the way to the testing facility, we idly prepared by chatting in the back seat, with a break for a bowl of ramen, about the pervasiveness of toxicity in our lives and the difficulty of gauging what amounts were deemed safe. How safe are cell phones? How much radiation from the plane ride over? How much radiation is there in Hong Kong compared to Tokyo? Or in New York City, so near to the Indian Point nuclear power plant? How much radiation does one receive from someone sleeping next to you? And who the hell gets the lucky job of standing guard at the 50km exclusion zone in Fukushima?

We arrived in the parking lot of a basic shed-like building. Natural Harmony is a company that sells produce direct to markets and grocery stores, after pooling from about 200 independent farmers. Of these farmers, about 100 are farming completely "natural", meaning they use no chemicals in growing their produce. The company offers to pre-sell all of a farmer's crop in hopes of gradually encouraging more small farmers to give up pesticides and chemical fertilizers. Natural Harmony also sells a few value-added products using natural rice and soy.

Photo by Kayoko Akabori

Photo by Kayoko Akabori

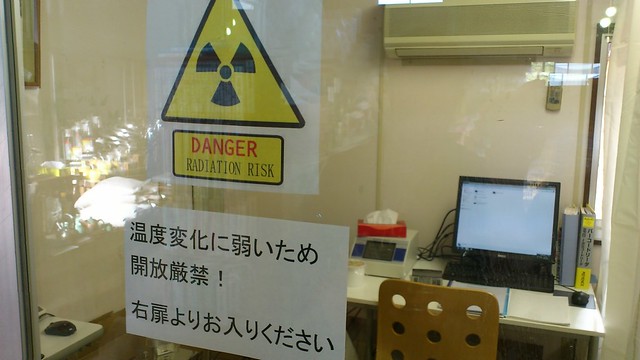

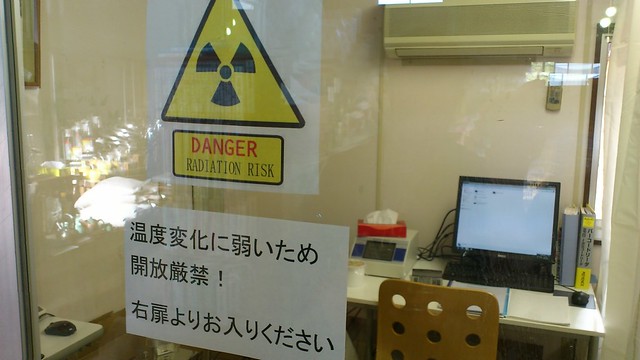

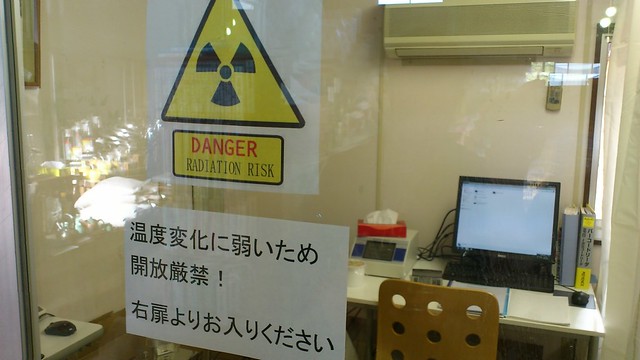

It seemed as if we were in their main hub of distribution and employees were busying themselves with packaging and sorting bags of rice and greens. We were kindly introduced to Takashi Oohashi and quickly led to a small side office with a prominent radiation risk warning stickered to the window!

Photo by Sam White

Photo by Sam White

After meeting a technician who was running radiation tests, the translated conversation turned directly to "the accident" and the testing process.

Photo by Sam White

Photo by Sam White

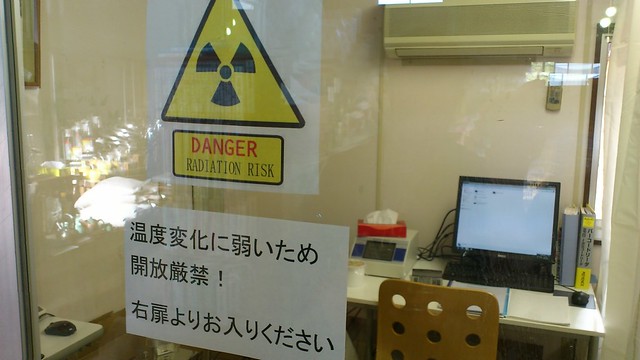

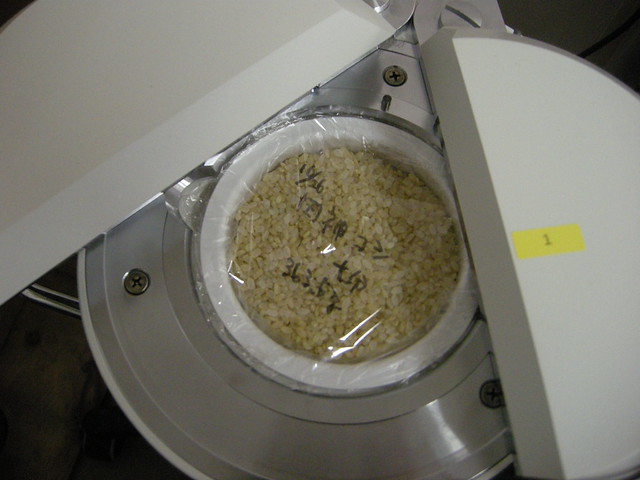

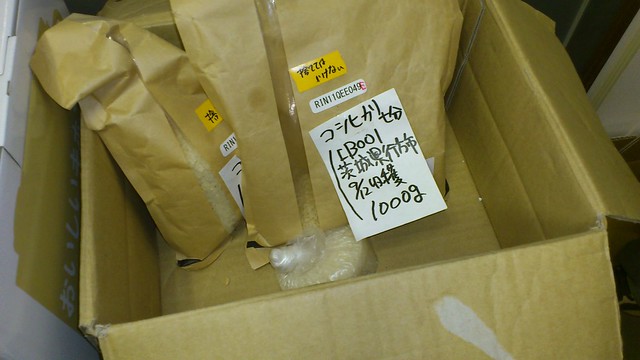

The equipment being used was two-month old technology and used samples of food packed to the approximate density of water (1g/ml). The accuracy of the reading was dependent upon the accuracy to that density, which made rice an easier sample than, say, taro root. This restriction brought up the subject of the new needs of such technology, and the hope that the technology becomes more accurate and versatile in the near future.

The testing equipment itself looked like a compact hunk of shining silver sitting at our feet, with a simple dial, a couple of protruding wires and a thermometer resting upon it. The equipment was approximately a $40,000 dollar investment for Natural Harmony and was manufactured by a company called EMF (Environment Measurement Family Japan).

We were lucky to witness a couple of tests, which take about 15 minutes to complete, of rice samples from a third party taken from areas near and around Natural Harmony farms. We were told that the government at first restricted these rice purchases and samples and had recently released those restrictions. Thus, these tests were helping prepare the first real life view of the initial effects of the accident.

Photo by Sam White

Photo by Sam White

Photo by Kayoko Akabori

Photo by Kayoko Akabori

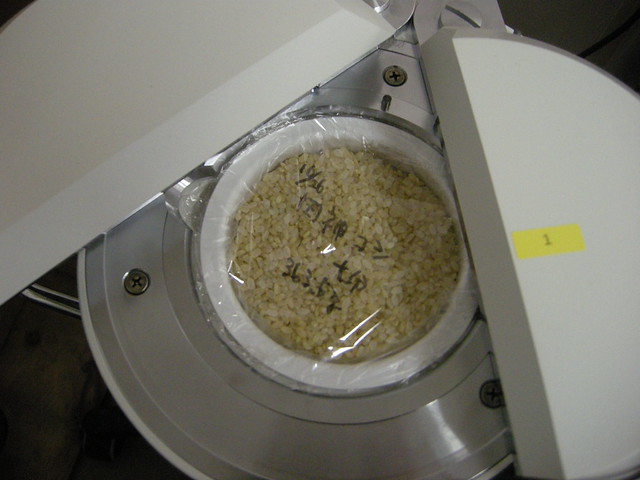

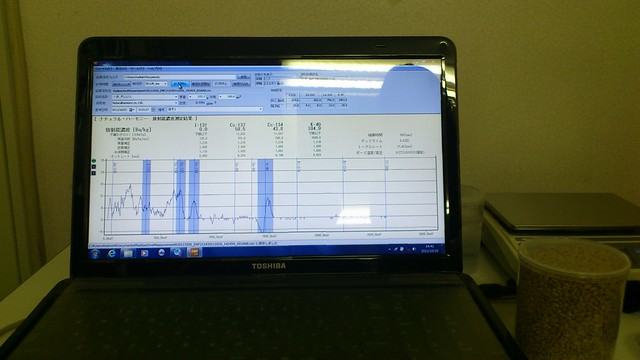

The machine was linked to a laptop and gave a graph-like and numerical reading of four isotope amounts. The two most significant readings seemed to be that of cesium-137 and cesium-134. Iodine and Potassium isotopes were also included. Due to my lack of fluency in Japanese and chemistry, I apologize to not understand all of the details of the readings! But I do understand that the tests do give give a number, in

becquerel's per kilogram (Bq/kg), and it is what this number means that is most intriguing.

Photo by Sam White

Photo by Sam White

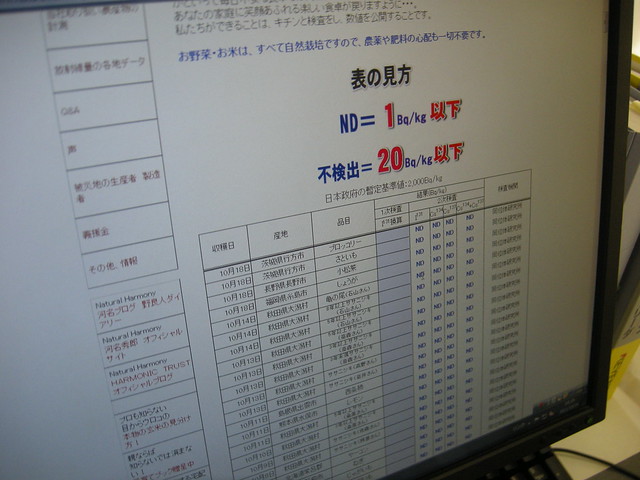

In a state of fear and confusion, it seems we are all put at ease if we can affix our idea of safety to a number. But what number? Natural Harmony has created a company standard for their customers at restricting safe produce to under 20 Becquerel's per kilogram. In addition to running tests on the produce, the company also has available in PDF format thru their website all test results of any produce for sale.

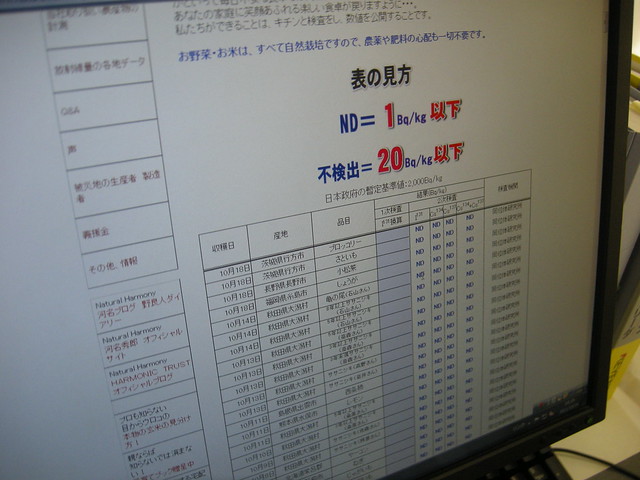

Natural Harmony website, where all the results of their tested produce is displayed. All info can be downloaded in PDF format. Photo by Kayoko Akabori

Natural Harmony website, where all the results of their tested produce is displayed. All info can be downloaded in PDF format. Photo by Kayoko Akabori

In comparison, the World Health Organization set the cut-off limit at a relatively much higher level of 350 Bq/kg. And furthermore, the Japanese government has set the safe level of contamination at 500 Bq/kg. Which should set off some alarms considering the discrepencies between a private, seemingly well-intentioned, accountable company setting a healthy limit at 20Bq/kg. and the government setting the safe limit 2500% higher. Without claiming to understand the complete situation or science, it seems like a classic case of creating a solution to a problem by the government simply creating a low standard for detection results. It also confirmed earlier answers of distrust when we simply asked what the company and farmers thought of the government and

TEPCO. Within our presence, one sample registered as ND (non-detected) but another had levels of cesium at 110 Bq/kg. and thus deemed unsafe for sale by Natural Harmony.

We asked about the methods of sampling and creating baselines and Natural Harmony explained testing rice from Kishu and other locations a long distance from Fukushima and of taking samples from all corners of their farmers fields. It is clear though, that there is still a small percentage of rice and produce that is actually being tested and that a clear map of the situation is years off. Especially if the expressed distrust in the government proves to be validated by a lack of transparency and a rush to sweep the problems under the rug in the name of commerce or irresponsibility.

Speaking of irresponsibility, it is clear no one really knows what to do with any contaminated food or samples. We were told of a sample of spinach coming back with "very high" levels of radioactivity and the government not responding to Natural Harmony's notification of results or request for help in disposal/handling. We asked what Natural Harmony now does with contaminated rice samples and they either store it or if contamination is low enough (under 20Bq/kg), it is offered to healthy employees to take home to eat at their own discretion (no children though!). The question of contaminated samples and its handling also brought up the issue of compost health. There is a great possibility that much of the contaminated produce harvested around the nuclear accident ended up back in the garbage and compost system after it hastily went to market. Also, we were told that much of Japan's organic compost material is derived from the very questionable rice bran of the Fukushima breadbasket.

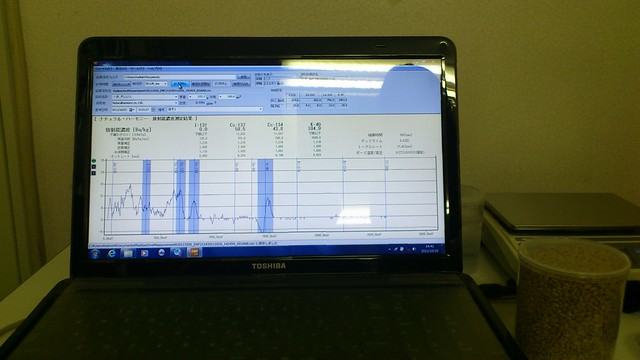

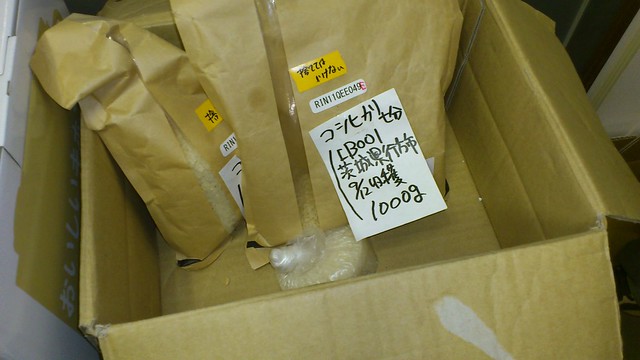

Rice to be tested. Photo by Sam White

Rice to be tested. Photo by Sam White

Natural Harmony made it clear that radioactive contamination is a great concern of their customers and is smartly doing a service to them and the farmers by testing. Contamination is more important an issue than organic versus chemically raised produce at the moment, but by dealing with small independent farmers Natural Harmony can better assure food safety by knowing its source. And any market swaying from Japan Agriculture (JA)-regulated, large scale, chemical farming towards local and natural farming seems positive despite the tragic motivations. We asked about any standardized labeling for test results and they said there was no plan, but that customers could find all information on the website or ask questions over the phone. They do have a private labeling standard for their natrual products, which are described on the packaging as Harmonic Foods. Hopefully this focus on the contents and toxicity of produce will lead to more widespread customer awareness in the value of natural, locally grown food. We asked about soil testing and those results were not in, but will certainly bring more complex questions and dilemmas when they are. Again, hopefully the added awareness of soil health and future will help transform this tragic moment into a positive movement and facilitate more customers demand for natural food and more reward for the few farmers taking the risk of giving up status quo, industrial farming.

Toshiya Yoshikai, Takashi Oohashi, Sam White, Howie Correa. Photo by Kayoko Akabori

Toshiya Yoshikai, Takashi Oohashi, Sam White, Howie Correa. Photo by Kayoko Akabori

It was clear there is obviously a long, tragic way to understand the scale and solutions to the contamination. I was also moved to wonder about the livelihoods of the farmers from the affected areas and not knowing what sort of support or compensation exists for them. It was certainly a reminder that the joy of harvest and being connected to the earth and soil takes on a dark flip-side at this moment in Japan. A lot of the fears are closely related to the unclear and unseen path of radiation, its concentrations and nature. But, I was stoked to meet folks from a small company making the steps to help in the important work of natural farming and of building more transparency into the landscape of post-"accident" agriculture.

*Howie Correa happily splits his year between Sacramento, CA, OPENrestaurant, Chez Panisse in Berkeley, CA, and Market Restaurant in Gloucester, MA.

**This post was originally posted on www.openharvestjapan.com on November 1, 2011.

By Howie Correa

Within half a day of arrival from Ireland, I was excited to be heading out of endless Tokyo to visit a radiation testing facility at Natural Harmony, a produce distribution site in Chiba. It was a trip that seemed to be at the heart of understanding the dilemma within this year's Japanese fall harvest, post-3/11, and all the ideas to be explored through OPENharvest.

Hours earlier, I had shared in the Ebisu-soaked joy and celebration side of being in Japan with a gang of creative, cross-continent collaborators. There was and is much to feel elated about, in recognizing connections through farms, food, wine and art. But zipping along in a sporty, yellow Volvo towards Chiba, to discuss radioactive contamination made one realize that Japan is dealing with very surreal, yet serious and specific everyday fears.

On the way to the testing facility, we idly prepared by chatting in the back seat, with a break for a bowl of ramen, about the pervasiveness of toxicity in our lives and the difficulty of gauging what amounts were deemed safe. How safe are cell phones? How much radiation from the plane ride over? How much radiation is there in Hong Kong compared to Tokyo? Or in New York City, so near to the Indian Point nuclear power plant? How much radiation does one receive from someone sleeping next to you? And who the hell gets the lucky job of standing guard at the 50km exclusion zone in Fukushima?

We arrived in the parking lot of a basic shed-like building. Natural Harmony is a company that sells produce direct to markets and grocery stores, after pooling from about 200 independent farmers. Of these farmers, about 100 are farming completely "natural", meaning they use no chemicals in growing their produce. The company offers to pre-sell all of a farmer's crop in hopes of gradually encouraging more small farmers to give up pesticides and chemical fertilizers. Natural Harmony also sells a few value-added products using natural rice and soy.

By Howie Correa

Within half a day of arrival from Ireland, I was excited to be heading out of endless Tokyo to visit a radiation testing facility at Natural Harmony, a produce distribution site in Chiba. It was a trip that seemed to be at the heart of understanding the dilemma within this year's Japanese fall harvest, post-3/11, and all the ideas to be explored through OPENharvest.

Hours earlier, I had shared in the Ebisu-soaked joy and celebration side of being in Japan with a gang of creative, cross-continent collaborators. There was and is much to feel elated about, in recognizing connections through farms, food, wine and art. But zipping along in a sporty, yellow Volvo towards Chiba, to discuss radioactive contamination made one realize that Japan is dealing with very surreal, yet serious and specific everyday fears.

On the way to the testing facility, we idly prepared by chatting in the back seat, with a break for a bowl of ramen, about the pervasiveness of toxicity in our lives and the difficulty of gauging what amounts were deemed safe. How safe are cell phones? How much radiation from the plane ride over? How much radiation is there in Hong Kong compared to Tokyo? Or in New York City, so near to the Indian Point nuclear power plant? How much radiation does one receive from someone sleeping next to you? And who the hell gets the lucky job of standing guard at the 50km exclusion zone in Fukushima?

We arrived in the parking lot of a basic shed-like building. Natural Harmony is a company that sells produce direct to markets and grocery stores, after pooling from about 200 independent farmers. Of these farmers, about 100 are farming completely "natural", meaning they use no chemicals in growing their produce. The company offers to pre-sell all of a farmer's crop in hopes of gradually encouraging more small farmers to give up pesticides and chemical fertilizers. Natural Harmony also sells a few value-added products using natural rice and soy.

Photo by Kayoko Akabori

It seemed as if we were in their main hub of distribution and employees were busying themselves with packaging and sorting bags of rice and greens. We were kindly introduced to Takashi Oohashi and quickly led to a small side office with a prominent radiation risk warning stickered to the window!

Photo by Kayoko Akabori

It seemed as if we were in their main hub of distribution and employees were busying themselves with packaging and sorting bags of rice and greens. We were kindly introduced to Takashi Oohashi and quickly led to a small side office with a prominent radiation risk warning stickered to the window!

Photo by Sam White

After meeting a technician who was running radiation tests, the translated conversation turned directly to "the accident" and the testing process.

Photo by Sam White

After meeting a technician who was running radiation tests, the translated conversation turned directly to "the accident" and the testing process.

Photo by Sam White

The equipment being used was two-month old technology and used samples of food packed to the approximate density of water (1g/ml). The accuracy of the reading was dependent upon the accuracy to that density, which made rice an easier sample than, say, taro root. This restriction brought up the subject of the new needs of such technology, and the hope that the technology becomes more accurate and versatile in the near future.

The testing equipment itself looked like a compact hunk of shining silver sitting at our feet, with a simple dial, a couple of protruding wires and a thermometer resting upon it. The equipment was approximately a $40,000 dollar investment for Natural Harmony and was manufactured by a company called EMF (Environment Measurement Family Japan).

We were lucky to witness a couple of tests, which take about 15 minutes to complete, of rice samples from a third party taken from areas near and around Natural Harmony farms. We were told that the government at first restricted these rice purchases and samples and had recently released those restrictions. Thus, these tests were helping prepare the first real life view of the initial effects of the accident.

Photo by Sam White

The equipment being used was two-month old technology and used samples of food packed to the approximate density of water (1g/ml). The accuracy of the reading was dependent upon the accuracy to that density, which made rice an easier sample than, say, taro root. This restriction brought up the subject of the new needs of such technology, and the hope that the technology becomes more accurate and versatile in the near future.

The testing equipment itself looked like a compact hunk of shining silver sitting at our feet, with a simple dial, a couple of protruding wires and a thermometer resting upon it. The equipment was approximately a $40,000 dollar investment for Natural Harmony and was manufactured by a company called EMF (Environment Measurement Family Japan).

We were lucky to witness a couple of tests, which take about 15 minutes to complete, of rice samples from a third party taken from areas near and around Natural Harmony farms. We were told that the government at first restricted these rice purchases and samples and had recently released those restrictions. Thus, these tests were helping prepare the first real life view of the initial effects of the accident.

Photo by Sam White

Photo by Sam White

Photo by Kayoko Akabori

The machine was linked to a laptop and gave a graph-like and numerical reading of four isotope amounts. The two most significant readings seemed to be that of cesium-137 and cesium-134. Iodine and Potassium isotopes were also included. Due to my lack of fluency in Japanese and chemistry, I apologize to not understand all of the details of the readings! But I do understand that the tests do give give a number, in becquerel's per kilogram (Bq/kg), and it is what this number means that is most intriguing.

Photo by Kayoko Akabori

The machine was linked to a laptop and gave a graph-like and numerical reading of four isotope amounts. The two most significant readings seemed to be that of cesium-137 and cesium-134. Iodine and Potassium isotopes were also included. Due to my lack of fluency in Japanese and chemistry, I apologize to not understand all of the details of the readings! But I do understand that the tests do give give a number, in becquerel's per kilogram (Bq/kg), and it is what this number means that is most intriguing.

Photo by Sam White

In a state of fear and confusion, it seems we are all put at ease if we can affix our idea of safety to a number. But what number? Natural Harmony has created a company standard for their customers at restricting safe produce to under 20 Becquerel's per kilogram. In addition to running tests on the produce, the company also has available in PDF format thru their website all test results of any produce for sale.

Photo by Sam White

In a state of fear and confusion, it seems we are all put at ease if we can affix our idea of safety to a number. But what number? Natural Harmony has created a company standard for their customers at restricting safe produce to under 20 Becquerel's per kilogram. In addition to running tests on the produce, the company also has available in PDF format thru their website all test results of any produce for sale.

Natural Harmony website, where all the results of their tested produce is displayed. All info can be downloaded in PDF format. Photo by Kayoko Akabori

In comparison, the World Health Organization set the cut-off limit at a relatively much higher level of 350 Bq/kg. And furthermore, the Japanese government has set the safe level of contamination at 500 Bq/kg. Which should set off some alarms considering the discrepencies between a private, seemingly well-intentioned, accountable company setting a healthy limit at 20Bq/kg. and the government setting the safe limit 2500% higher. Without claiming to understand the complete situation or science, it seems like a classic case of creating a solution to a problem by the government simply creating a low standard for detection results. It also confirmed earlier answers of distrust when we simply asked what the company and farmers thought of the government and TEPCO. Within our presence, one sample registered as ND (non-detected) but another had levels of cesium at 110 Bq/kg. and thus deemed unsafe for sale by Natural Harmony.

We asked about the methods of sampling and creating baselines and Natural Harmony explained testing rice from Kishu and other locations a long distance from Fukushima and of taking samples from all corners of their farmers fields. It is clear though, that there is still a small percentage of rice and produce that is actually being tested and that a clear map of the situation is years off. Especially if the expressed distrust in the government proves to be validated by a lack of transparency and a rush to sweep the problems under the rug in the name of commerce or irresponsibility.

Speaking of irresponsibility, it is clear no one really knows what to do with any contaminated food or samples. We were told of a sample of spinach coming back with "very high" levels of radioactivity and the government not responding to Natural Harmony's notification of results or request for help in disposal/handling. We asked what Natural Harmony now does with contaminated rice samples and they either store it or if contamination is low enough (under 20Bq/kg), it is offered to healthy employees to take home to eat at their own discretion (no children though!). The question of contaminated samples and its handling also brought up the issue of compost health. There is a great possibility that much of the contaminated produce harvested around the nuclear accident ended up back in the garbage and compost system after it hastily went to market. Also, we were told that much of Japan's organic compost material is derived from the very questionable rice bran of the Fukushima breadbasket.

Natural Harmony website, where all the results of their tested produce is displayed. All info can be downloaded in PDF format. Photo by Kayoko Akabori

In comparison, the World Health Organization set the cut-off limit at a relatively much higher level of 350 Bq/kg. And furthermore, the Japanese government has set the safe level of contamination at 500 Bq/kg. Which should set off some alarms considering the discrepencies between a private, seemingly well-intentioned, accountable company setting a healthy limit at 20Bq/kg. and the government setting the safe limit 2500% higher. Without claiming to understand the complete situation or science, it seems like a classic case of creating a solution to a problem by the government simply creating a low standard for detection results. It also confirmed earlier answers of distrust when we simply asked what the company and farmers thought of the government and TEPCO. Within our presence, one sample registered as ND (non-detected) but another had levels of cesium at 110 Bq/kg. and thus deemed unsafe for sale by Natural Harmony.

We asked about the methods of sampling and creating baselines and Natural Harmony explained testing rice from Kishu and other locations a long distance from Fukushima and of taking samples from all corners of their farmers fields. It is clear though, that there is still a small percentage of rice and produce that is actually being tested and that a clear map of the situation is years off. Especially if the expressed distrust in the government proves to be validated by a lack of transparency and a rush to sweep the problems under the rug in the name of commerce or irresponsibility.

Speaking of irresponsibility, it is clear no one really knows what to do with any contaminated food or samples. We were told of a sample of spinach coming back with "very high" levels of radioactivity and the government not responding to Natural Harmony's notification of results or request for help in disposal/handling. We asked what Natural Harmony now does with contaminated rice samples and they either store it or if contamination is low enough (under 20Bq/kg), it is offered to healthy employees to take home to eat at their own discretion (no children though!). The question of contaminated samples and its handling also brought up the issue of compost health. There is a great possibility that much of the contaminated produce harvested around the nuclear accident ended up back in the garbage and compost system after it hastily went to market. Also, we were told that much of Japan's organic compost material is derived from the very questionable rice bran of the Fukushima breadbasket.

Rice to be tested. Photo by Sam White

Natural Harmony made it clear that radioactive contamination is a great concern of their customers and is smartly doing a service to them and the farmers by testing. Contamination is more important an issue than organic versus chemically raised produce at the moment, but by dealing with small independent farmers Natural Harmony can better assure food safety by knowing its source. And any market swaying from Japan Agriculture (JA)-regulated, large scale, chemical farming towards local and natural farming seems positive despite the tragic motivations. We asked about any standardized labeling for test results and they said there was no plan, but that customers could find all information on the website or ask questions over the phone. They do have a private labeling standard for their natrual products, which are described on the packaging as Harmonic Foods. Hopefully this focus on the contents and toxicity of produce will lead to more widespread customer awareness in the value of natural, locally grown food. We asked about soil testing and those results were not in, but will certainly bring more complex questions and dilemmas when they are. Again, hopefully the added awareness of soil health and future will help transform this tragic moment into a positive movement and facilitate more customers demand for natural food and more reward for the few farmers taking the risk of giving up status quo, industrial farming.

Rice to be tested. Photo by Sam White

Natural Harmony made it clear that radioactive contamination is a great concern of their customers and is smartly doing a service to them and the farmers by testing. Contamination is more important an issue than organic versus chemically raised produce at the moment, but by dealing with small independent farmers Natural Harmony can better assure food safety by knowing its source. And any market swaying from Japan Agriculture (JA)-regulated, large scale, chemical farming towards local and natural farming seems positive despite the tragic motivations. We asked about any standardized labeling for test results and they said there was no plan, but that customers could find all information on the website or ask questions over the phone. They do have a private labeling standard for their natrual products, which are described on the packaging as Harmonic Foods. Hopefully this focus on the contents and toxicity of produce will lead to more widespread customer awareness in the value of natural, locally grown food. We asked about soil testing and those results were not in, but will certainly bring more complex questions and dilemmas when they are. Again, hopefully the added awareness of soil health and future will help transform this tragic moment into a positive movement and facilitate more customers demand for natural food and more reward for the few farmers taking the risk of giving up status quo, industrial farming.

Toshiya Yoshikai, Takashi Oohashi, Sam White, Howie Correa. Photo by Kayoko Akabori

It was clear there is obviously a long, tragic way to understand the scale and solutions to the contamination. I was also moved to wonder about the livelihoods of the farmers from the affected areas and not knowing what sort of support or compensation exists for them. It was certainly a reminder that the joy of harvest and being connected to the earth and soil takes on a dark flip-side at this moment in Japan. A lot of the fears are closely related to the unclear and unseen path of radiation, its concentrations and nature. But, I was stoked to meet folks from a small company making the steps to help in the important work of natural farming and of building more transparency into the landscape of post-"accident" agriculture.

*Howie Correa happily splits his year between Sacramento, CA, OPENrestaurant, Chez Panisse in Berkeley, CA, and Market Restaurant in Gloucester, MA.

**This post was originally posted on www.openharvestjapan.com on November 1, 2011.

Toshiya Yoshikai, Takashi Oohashi, Sam White, Howie Correa. Photo by Kayoko Akabori

It was clear there is obviously a long, tragic way to understand the scale and solutions to the contamination. I was also moved to wonder about the livelihoods of the farmers from the affected areas and not knowing what sort of support or compensation exists for them. It was certainly a reminder that the joy of harvest and being connected to the earth and soil takes on a dark flip-side at this moment in Japan. A lot of the fears are closely related to the unclear and unseen path of radiation, its concentrations and nature. But, I was stoked to meet folks from a small company making the steps to help in the important work of natural farming and of building more transparency into the landscape of post-"accident" agriculture.

*Howie Correa happily splits his year between Sacramento, CA, OPENrestaurant, Chez Panisse in Berkeley, CA, and Market Restaurant in Gloucester, MA.

**This post was originally posted on www.openharvestjapan.com on November 1, 2011.

Comments (0)

There are no comments for this article. Be the first one to leave a message!