The eskimos have many words for snow, just like the Japanese have many words for seaweed.

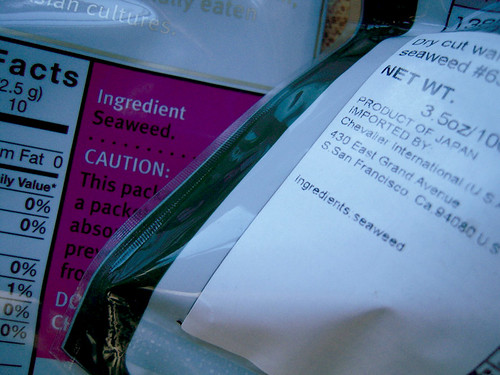

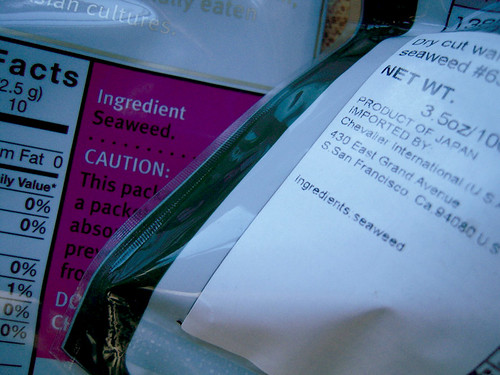

For those of us on the other side of the pacific, the lack of words for seaweed is problematic. It is very confusing when reading the translated English ingredients for

nori, iwanori, wakame and

kombu since they all say "seaweed."

It's kind of like listing the ingredients for a bag of frozen shrimp and pack of smoked salmon as "seafood." Totally different foods with totally different applications.

There have been a few times when people have asked me what all these different types of "seaweed" are used for - so I will attempt to explain here. I am going to describe the different types from soft to hard.

Iwanori (Porphyra Yezoensis)

Iwanori (Porphyra Yezoensis)

Iwanori

Iwanori literally means "rock seaweed" because it is found in the crevices of rocks. Like regular

nori (see below) it is dried and eaten. It's very soft and delicate - almost like dried out lace. It's excellent to sprinkle on pasta, soba and tofu.

Iwanori is much more aromatic than

nori. I would almost say that it's the veal of

nori. It's greener and falls apart in your mouth quicker.

Kids who grew up on Japanese condiments laden with MSG are usually fond of

iwanori tsukudani from the brand

Gohandesuyo.

Nori (Porphyra)

This is probably the type of seaweed that people see the most in the U.S. We are crazy about rolls in the U.S. so we must be crazy about

nori too.

Nori, sometimes referred to as laver, is made out of red alga.

Nori is produced by a drying process and comes in neat square or rectangle sheets.

Although most commonly seen as the "black wrapping" of a roll,

nori is also great right out of the bag. The crispy texture is irressistable. Unlike some other types of "seaweed" you do not soak

nori in water. If you do so - it will fall apart.

Nori with Megumi Natto, Shiso, Ume and Rice

Wakame (Undaria pinnatifida)

Wakame (Undaria pinnatifida)

Wakame

Wakame is made from a sea vegetable called Undaria pinnatifida. That's a mouthful.

Wakame is most commonly seen in miso soup. Before that stage, however, it's usually dry (at least in the states) and rehydrated.

Wakame must be hydrated and consumed, unless you like scratch marks on your esophagus.

Dry

wakame is super convenient because it never goes bad. When I don't have salad greens on hand, I can always rely on these shriveled dudes for a fantastic wa-fu salad.

If you get a mouthful of hydrated Undaria pinnatifida in your mouth, you will find it to be slippery and potentially slimy. The texture is the pull here - since it doesn't taste very strong. Thicker parts of the

wakame can be described as crunchy or "kori kori" in Japanese.

Wakame in

Sunomono

Kombu (Saccharina japonica)

Kombu (Saccharina japonica)

The liquid of the gods in a Japanese kitchen is dashi. And good dashi begins with

kombu. Kombu is the toughest of all four seaweeds introduced today and like

wakame, it is always rehydrated.

It is often not consumed directly (even after hydration), but used for stock-making. Some exceptions to eating the actual

kombu are for oden and battera sushi.

I use

kombu every week to make my dashi. It must be soaked in water for a minimum of 20 minutes, uncovered, before it is exposed to a heat source.

Kombu provides the base for many things umami-related in Japanese cuisine.

Here's a little fact from

wikipedia about

kombu and the Okinawa prefecture which enjoys the title of having the world's longest life expectancy:

Traditional Okinawan cuisine relies heavily on kombu as a part of the diet; this practice began in the Edo period. Okinawa uses more kombu per household than any other prefecture.

Kombu in

Dashi

There are still so many types of seaweed that are in the Japanese diet, but I would say that

nori, wakame and

kombu are the three that I consume on a daily basis.

Having a bunch of words for snow may be useless in umamiland, but it's certainly not useless to have a bunch of words for seaweed.

The eskimos have many words for snow, just like the Japanese have many words for seaweed.

For those of us on the other side of the pacific, the lack of words for seaweed is problematic. It is very confusing when reading the translated English ingredients for nori, iwanori, wakame and kombu since they all say "seaweed."

The eskimos have many words for snow, just like the Japanese have many words for seaweed.

For those of us on the other side of the pacific, the lack of words for seaweed is problematic. It is very confusing when reading the translated English ingredients for nori, iwanori, wakame and kombu since they all say "seaweed."

It's kind of like listing the ingredients for a bag of frozen shrimp and pack of smoked salmon as "seafood." Totally different foods with totally different applications.

It's kind of like listing the ingredients for a bag of frozen shrimp and pack of smoked salmon as "seafood." Totally different foods with totally different applications.

There have been a few times when people have asked me what all these different types of "seaweed" are used for - so I will attempt to explain here. I am going to describe the different types from soft to hard.

There have been a few times when people have asked me what all these different types of "seaweed" are used for - so I will attempt to explain here. I am going to describe the different types from soft to hard.

Iwanori (Porphyra Yezoensis)

Iwanori (Porphyra Yezoensis)

Iwanori literally means "rock seaweed" because it is found in the crevices of rocks. Like regular nori (see below) it is dried and eaten. It's very soft and delicate - almost like dried out lace. It's excellent to sprinkle on pasta, soba and tofu.

Iwanori is much more aromatic than nori. I would almost say that it's the veal of nori. It's greener and falls apart in your mouth quicker.

Kids who grew up on Japanese condiments laden with MSG are usually fond of iwanori tsukudani from the brand Gohandesuyo.

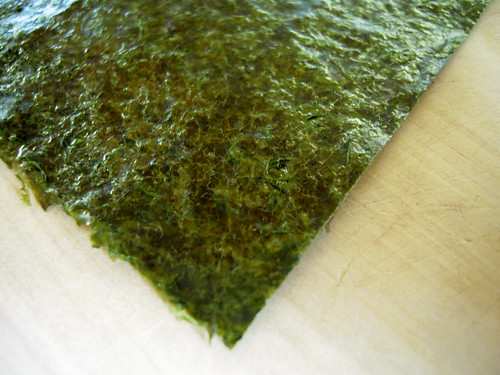

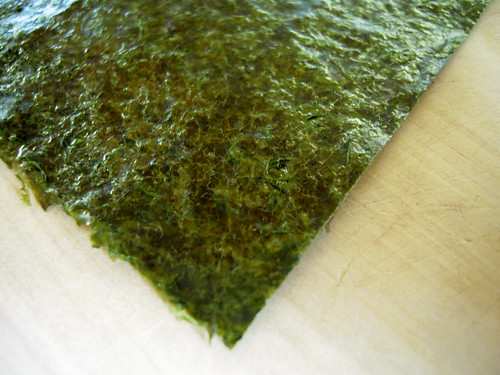

Nori (Porphyra)

Iwanori literally means "rock seaweed" because it is found in the crevices of rocks. Like regular nori (see below) it is dried and eaten. It's very soft and delicate - almost like dried out lace. It's excellent to sprinkle on pasta, soba and tofu.

Iwanori is much more aromatic than nori. I would almost say that it's the veal of nori. It's greener and falls apart in your mouth quicker.

Kids who grew up on Japanese condiments laden with MSG are usually fond of iwanori tsukudani from the brand Gohandesuyo.

Nori (Porphyra)

This is probably the type of seaweed that people see the most in the U.S. We are crazy about rolls in the U.S. so we must be crazy about nori too. Nori, sometimes referred to as laver, is made out of red alga. Nori is produced by a drying process and comes in neat square or rectangle sheets.

Although most commonly seen as the "black wrapping" of a roll, nori is also great right out of the bag. The crispy texture is irressistable. Unlike some other types of "seaweed" you do not soak nori in water. If you do so - it will fall apart.

Nori with Megumi Natto, Shiso, Ume and Rice

This is probably the type of seaweed that people see the most in the U.S. We are crazy about rolls in the U.S. so we must be crazy about nori too. Nori, sometimes referred to as laver, is made out of red alga. Nori is produced by a drying process and comes in neat square or rectangle sheets.

Although most commonly seen as the "black wrapping" of a roll, nori is also great right out of the bag. The crispy texture is irressistable. Unlike some other types of "seaweed" you do not soak nori in water. If you do so - it will fall apart.

Nori with Megumi Natto, Shiso, Ume and Rice

Wakame (Undaria pinnatifida)

Wakame (Undaria pinnatifida)

Wakame is made from a sea vegetable called Undaria pinnatifida. That's a mouthful.

Wakame is most commonly seen in miso soup. Before that stage, however, it's usually dry (at least in the states) and rehydrated. Wakame must be hydrated and consumed, unless you like scratch marks on your esophagus.

Wakame is made from a sea vegetable called Undaria pinnatifida. That's a mouthful.

Wakame is most commonly seen in miso soup. Before that stage, however, it's usually dry (at least in the states) and rehydrated. Wakame must be hydrated and consumed, unless you like scratch marks on your esophagus.

Dry wakame is super convenient because it never goes bad. When I don't have salad greens on hand, I can always rely on these shriveled dudes for a fantastic wa-fu salad.

If you get a mouthful of hydrated Undaria pinnatifida in your mouth, you will find it to be slippery and potentially slimy. The texture is the pull here - since it doesn't taste very strong. Thicker parts of the wakame can be described as crunchy or "kori kori" in Japanese.

Wakame in Sunomono

Dry wakame is super convenient because it never goes bad. When I don't have salad greens on hand, I can always rely on these shriveled dudes for a fantastic wa-fu salad.

If you get a mouthful of hydrated Undaria pinnatifida in your mouth, you will find it to be slippery and potentially slimy. The texture is the pull here - since it doesn't taste very strong. Thicker parts of the wakame can be described as crunchy or "kori kori" in Japanese.

Wakame in Sunomono

Kombu (Saccharina japonica)

Kombu (Saccharina japonica)

The liquid of the gods in a Japanese kitchen is dashi. And good dashi begins with kombu. Kombu is the toughest of all four seaweeds introduced today and like wakame, it is always rehydrated.

The liquid of the gods in a Japanese kitchen is dashi. And good dashi begins with kombu. Kombu is the toughest of all four seaweeds introduced today and like wakame, it is always rehydrated.

It is often not consumed directly (even after hydration), but used for stock-making. Some exceptions to eating the actual kombu are for oden and battera sushi.

I use kombu every week to make my dashi. It must be soaked in water for a minimum of 20 minutes, uncovered, before it is exposed to a heat source. Kombu provides the base for many things umami-related in Japanese cuisine.

It is often not consumed directly (even after hydration), but used for stock-making. Some exceptions to eating the actual kombu are for oden and battera sushi.

I use kombu every week to make my dashi. It must be soaked in water for a minimum of 20 minutes, uncovered, before it is exposed to a heat source. Kombu provides the base for many things umami-related in Japanese cuisine.

Here's a little fact from wikipedia about kombu and the Okinawa prefecture which enjoys the title of having the world's longest life expectancy:

Traditional Okinawan cuisine relies heavily on kombu as a part of the diet; this practice began in the Edo period. Okinawa uses more kombu per household than any other prefecture.

Kombu in Dashi

Here's a little fact from wikipedia about kombu and the Okinawa prefecture which enjoys the title of having the world's longest life expectancy:

Traditional Okinawan cuisine relies heavily on kombu as a part of the diet; this practice began in the Edo period. Okinawa uses more kombu per household than any other prefecture.

Kombu in Dashi

There are still so many types of seaweed that are in the Japanese diet, but I would say that nori, wakame and kombu are the three that I consume on a daily basis.

Having a bunch of words for snow may be useless in umamiland, but it's certainly not useless to have a bunch of words for seaweed.

There are still so many types of seaweed that are in the Japanese diet, but I would say that nori, wakame and kombu are the three that I consume on a daily basis.

Having a bunch of words for snow may be useless in umamiland, but it's certainly not useless to have a bunch of words for seaweed.

Comments (12)

Does your store carry shiro ita kombu? I have a very hard time finding it.

Alex – I think it can be “Kuki-Wakame”.

Does anyone know the type of seaweed that is served in japanese restaurants? I know its called seaweed salad, or hiyashi wakame. But I need to know the name of that specific bright neon green seaweed type, I know its called wakame, but when I try to buy wakame, its the different type of seaweed. Im trying to find that specific dried seaweed that seaweed salad is made from.

Hijiki safety concerns

Four countries have issued warnings, but no outright bans for hijiki, citing unacceptable levels of inorganic arsenic. The tests on hijiki which lead to warnings in the UK among other places was based on testing dried, un-soaked hijiki – and most people never eat hijiki that way. Soaking reduces the amount of trace arsenic by 1/7th; rinsing and cooking it in liquid further reduces it. The Japanese report by the Tokyo Health and Welfare Department states that as long as a person weighing 50kg (about 110lb) does not eat more than 5 servings of 5g dry weight of hijiki per day (which swells up to a lot more than that when soaked) will be perfectly safe, even pregnant women.

http://www.fukushihoken.metro.tokyo.jp/kenkou/anzen/anzen_info/others/hijiki/index.html

Great seaweed-off! I never really knew the particular differences but I feel a little more confident in the ’weed area.

(can you actually smoke this weed?)

A couple of days ago there was kind of a food scandal here in Denmark as a Danish company importing seaweed from Japan had found large amounts of arsenik in it. It was the kind called “Hijiki”(Hizikia fusiforme) which supposedly has the potential to contain this poison already when it is harvested in nature.

Do you know what this hijiki weed is used for in Japan? And is this a problem over there as well?

It’s actually a myth that the Inuit have many words for snow. They have generally about as many as we do in English, (snow, sleet, slush, etc.) Rather, Eskimo-Aleut languages are agglutinative which means they add different endings onto (in this case) a noun and it becomes a part of the word. So you can have a near infinite number different words for snow in that it’s the word snow plus a morpheme for case, mood, plurality, gender, as well as verbs and pronouns, often combining to be an entire one-word sentence.

Sorry to threadjack. As a linguist this particular misunderstanding is sort of a pet peeve of mine.

Craig – that is fascinating. Thank you very much for filling me in. I actually really love how I learn something new every time I write a post here. Whether it be about a linguistics issue or about a food scandal in Denmark involving hijiki (Thanks Anders for that)!

Hi

I speak Scottish Gaelic, and Ireland, Scotland and Wales Celtic language communities especially have a long tradition of using seaweeds in cooking and agriculture. Many Scottish island communities still spread seaweed on the land as a fertiliser and crofters feed it to their cattle.

MOst of the various types of Nori as you said are related to laver (porphyra),although it’s porphyra umbilicalis that is laver proper, and porphyra tenera which is the Japanese Nori most commonly used in sushi. Laver is an Atlantic seaweed.

The British, or Atlantic, equivalent to wakame is alaria esculenta, with the old fashioned names of badderlocks or henware in English. Known as “Mircean” in Scottish Gaelic.

Konbu are types of kelp, the larger darker types of seaweed(laminaria). Not to be confused with the industrial seaweed ash product which is also called Kelp.

One type of kelp that can be eaten raw is called sugar kelp (smeartan in Scots Gaelic)-laminaria saccharina- or Satou Konbu in Japanese.

There are also other edible types of seaweed used in Ireland and Scotland that I don’t know their japanese relatives for. Duileasg (Gaelic (Irish and Scottish) – a red seaweed – from which English “dulse” comes, cairgean – another red seaweed – from which Hiberno/Scottish English “carragheen” or “carrageen” comes, and the gelling agent carrageenan, is extracted from. Sea lettuce too.

Hope all this helps!

Hello Steafan,

Thank you do much for all of that information. There is a while wide world of seaweed out there to explore. It’s do interesting to me that Celtic communities are closely tied to seaweed. Do any of the communities extract broth from seaweed?

Hi, I was told that kombu and wakame were the same, I’m feeling confused. At an Asian market they told me to rinse and soak the kombu and then cut in strips. Is that right? Just want to add it to soup, (miso, udon) etc… thank you.